Facial Codes in Jewelry

From the Middle East to Africa, via India, Tibet and Bhutan, the world of facial piercings, such as septum, nostril or labret, have reached the West, introducing themselves as a sign of distinction and belonging

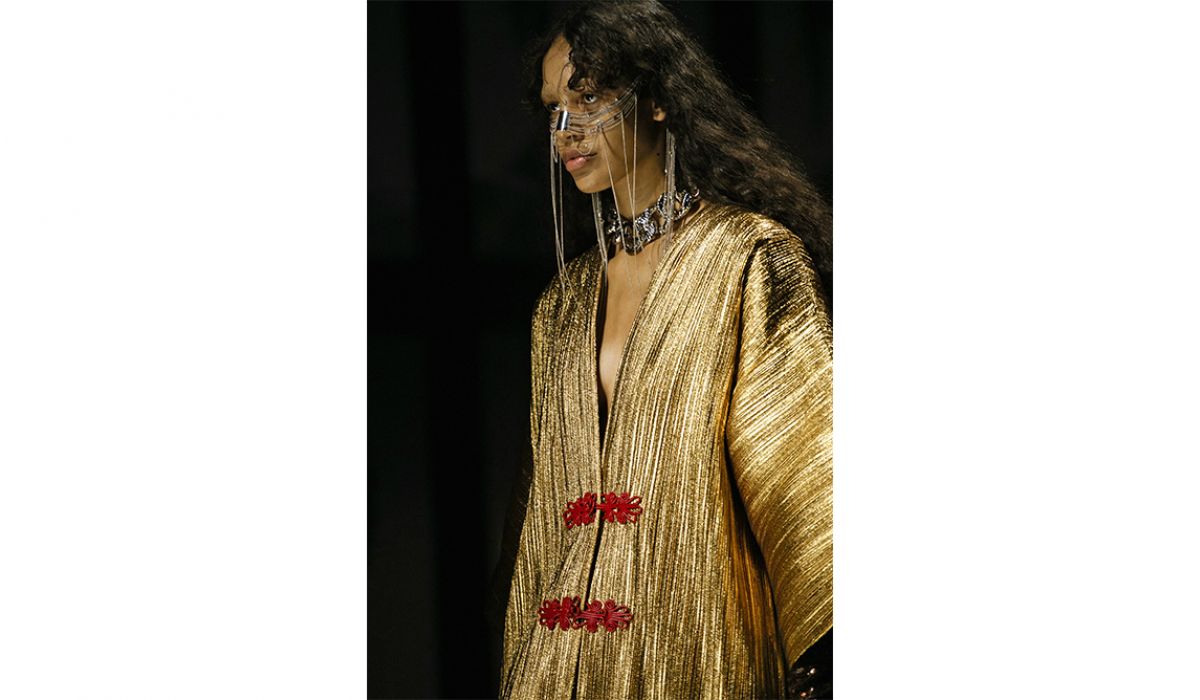

We are less and less surprised by the septum, nostril, labret, face and body piercings we see on the Givenchy, Balmain and Gucci catwalks and in the metropolitan squares of New York, London and Milan. It is a victory for facial jewel. A fan of these body-modifying decorations is Riccardo Tisci, who has been pursuing the septum look for Givenchy since the fall of 2015 with exponentially repeated piercings that culminated in a Goth-tribal look made of pearls, lace and jewels in the spring of 2016 in New York. Facial and body decorations are linked to ancestral traditions and animist beliefs that various peoples have continued over time. However, they have now become a way to summarize the state of being that we want to express in to society. These unusual decorations reveal the contemporary need to repossess our personal narrative. The tendency to flaunt them also shows a desire to retrieve ancestral gestures and a lost sign of belonging. Nostril piercing has been common among the nomadic tribes of the Middle East since ancient times, as well as among women in the Himalayan area of northern India, Nepal, Tibet and Bhutan, as a sign of their social status as married women, just as we do in our “faith”. Some African ethnic groups, such as the Toposa in South Sudan or the Nyangatom in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, practice scarification (scars obtained by inserting substances under the skin to create volume) to coincide with initiation rites of passage from childhood to adulthood. Each ethnic group had its own symbols to permanently alter their appearance and to protect themselves from demons and evil spirits. Women bore impressive scarring on their bellies, which also constituted their sexual attraction.

Miss Nepal 2016 Tenisa Rana during the annual celebrations of Nepali Culture in London, UK, on 28 August 2016. Photo @Alamy/IPA.

Miss Nepal 2016 Tenisa Rana during the annual celebrations of Nepali Culture in London, UK, on 28 August 2016. Photo @Alamy/IPA.

Scarification, tattoos and the insertion of a variety of objects into the skin, forerunners of our piercings, were seen as indicators of social position and rank, providing explicit information about each individual and distinguishing the roles of the various members within the ethnic group in order to regulate their relationships both during ritual ceremonies and in daily activities. In tribal societies, the surprising and symbolic object inserted into the body thus responded to the ancestral need to identify themselves with the group, a particular sign of recognition that distinguished them from others. Even in contemporary societies, in the 1970s and ‘80s, for example, those who adhered to punk, rocker and Goth currents of thought adopted septum piercing as an ideological manifesto precisely because of its semantic meaning as a symbol of defiance and rebellion against conservative values and as an assertion of independence in personal choices. Facial and body piercings, as well as tattoos, were a distinctive feature of so-called “deviant or subversive subcultures” and extreme experiments in body modification were such a widespread practice that, in some circles, it was considered a movement. The latter were extensively documented in the 1989 publication “Modern Primitives”, considered the “Body bible for underground movements”. Those “modern primitives” were people who participated in “contemporary rituals” that included face piercing, scarification and permanent markings. In the transition from modern to postmodern, facial jewels have lost their ritual value and been reinterpreted as a way to identify the individual because they produce identity and difference in one fell swoop, challenging the usual canons of aesthetic judgement and rigid models of perfection. In an era of excess individualism, marks and modifications are not seen as abnormal behavior but rather as an expression of personal taste, devoid of historical or cultural baggage. All jewelry, including facial decoration, is one of the most powerful symbolic means of defining our public image because it condenses multiple layers of meaning and tells the world who the person wearing it is.