The Preciousness Of Paper On Show

Alba Cappellieri, professor and director of Fashion Design degree courses at Milan Polytechnic, talks about the exhibition 'Paper Jewelry: the Preciousness of Fragility'

Paper is an extremely simple, poor and low resistant element of biological origin. Nowadays, however, also due to growing attention to sustainability, various recycling methods are being experimented that see paper playing a leading role in new cellulosic materials. Starting from a study that ranged from the characteristics of the material to assembly techniques, students at Milan Polytechnic, the best Italian university in the QS World University Ranking, worked on a design in which paper was reinterpreted, becoming as precious as an authentic and wearable jewel. From 10th April to 30th May, and therefore also during Design Week, Milan Polytechnic will be hosting the 'Paper Jewelry: the Preciousness of Fragility' exhibition, curated by Alba Cappellieri, professor and director of Fashion Design degree courses, to whom we posed a few questions.

What is the concept of the exhibition? What kind of approach do the students have in creating an item of jewelry with recycled material today?

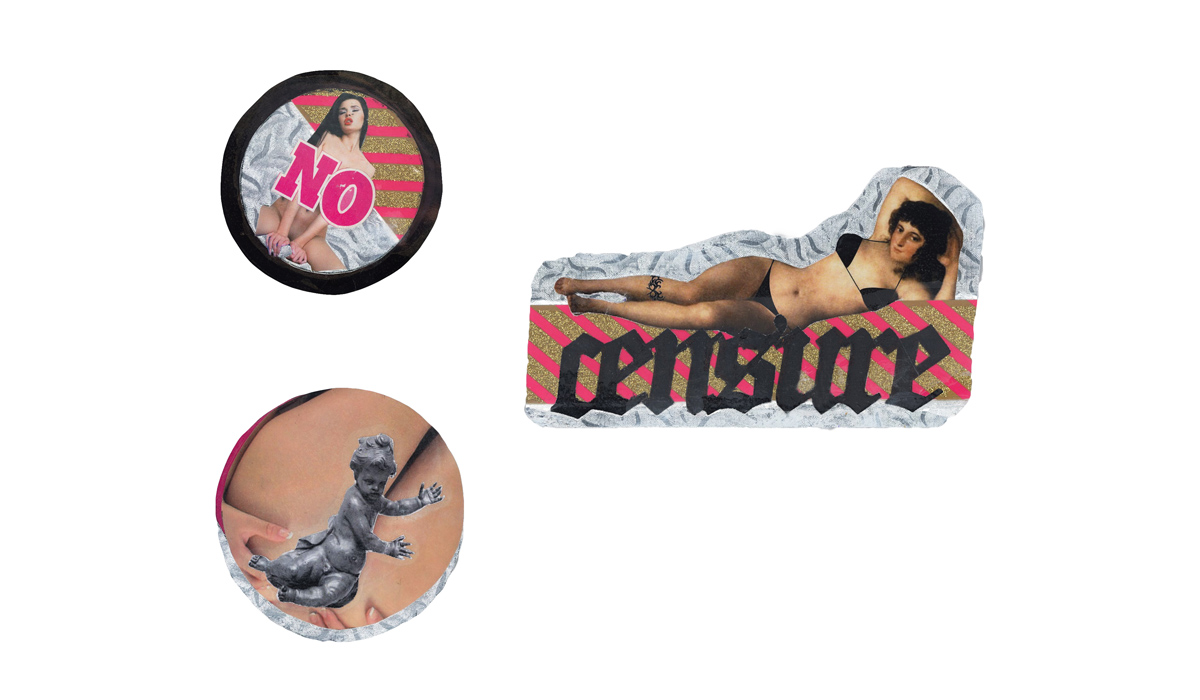

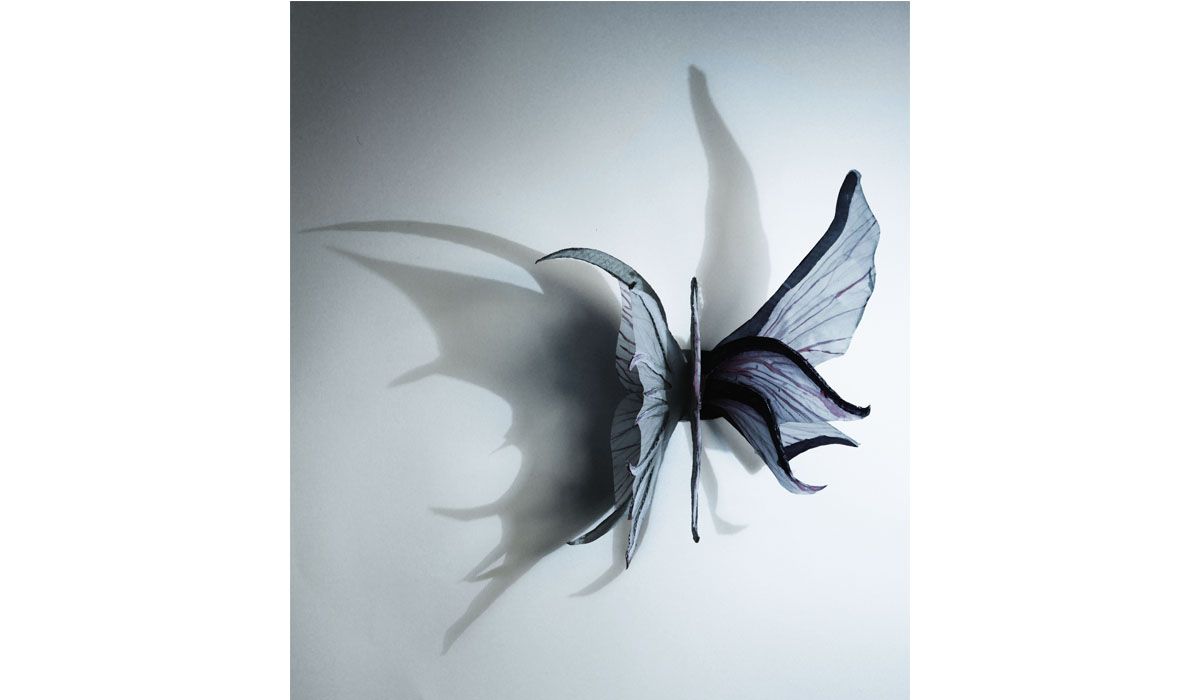

The concept of the exhibition arose from the desire to enhance the value of design as the result of experimentation and cross-fertilization and with the aim of investigating into languages and heterogeneous poetics that are normally a long way from those of traditional jewelry. The preciousness of the designs is not, in fact, linked to the intrinsic preciousness of the material used, but rather to the story they have to tell. The designs on display are the works of 40 students on Milan Polytechnic's Jewelry Design Course during which they followed design methods to achieve the design and creation of a jewelry item made of paper. Starting from a study that ranged from the characteristics of the material to assembly techniques, the students looked for inspiration for the design in the most varied of places: from music to literature, from nature to sculpture. And they transferred them onto the body in the form of jewelry.

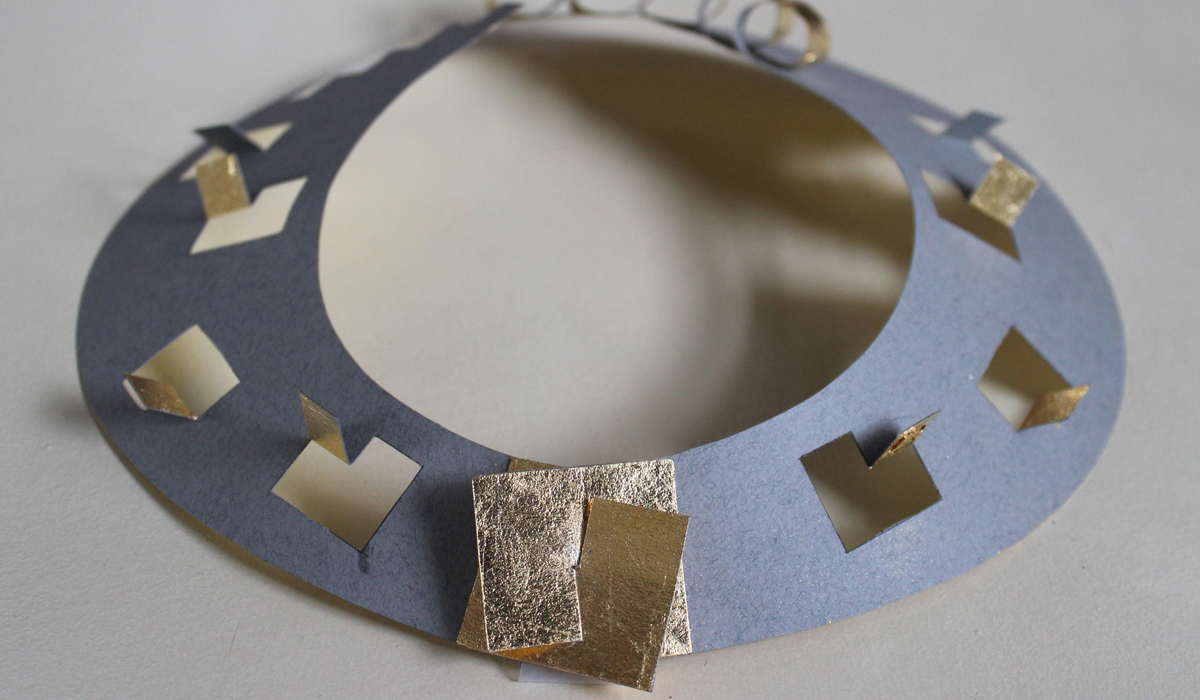

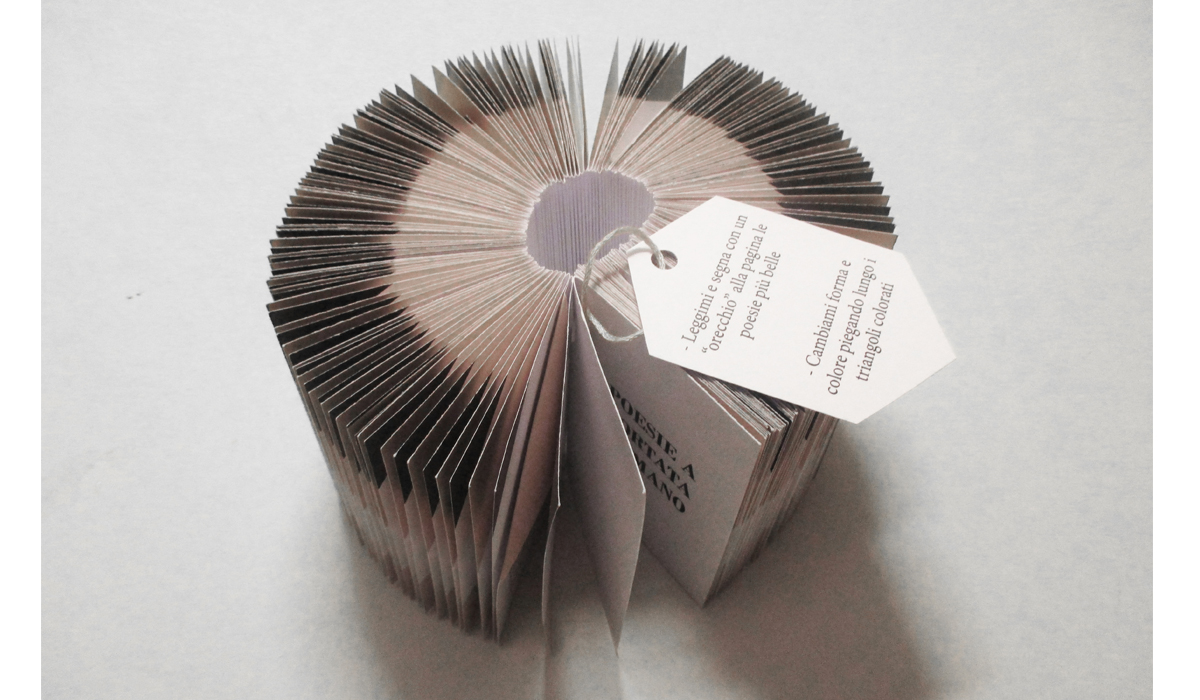

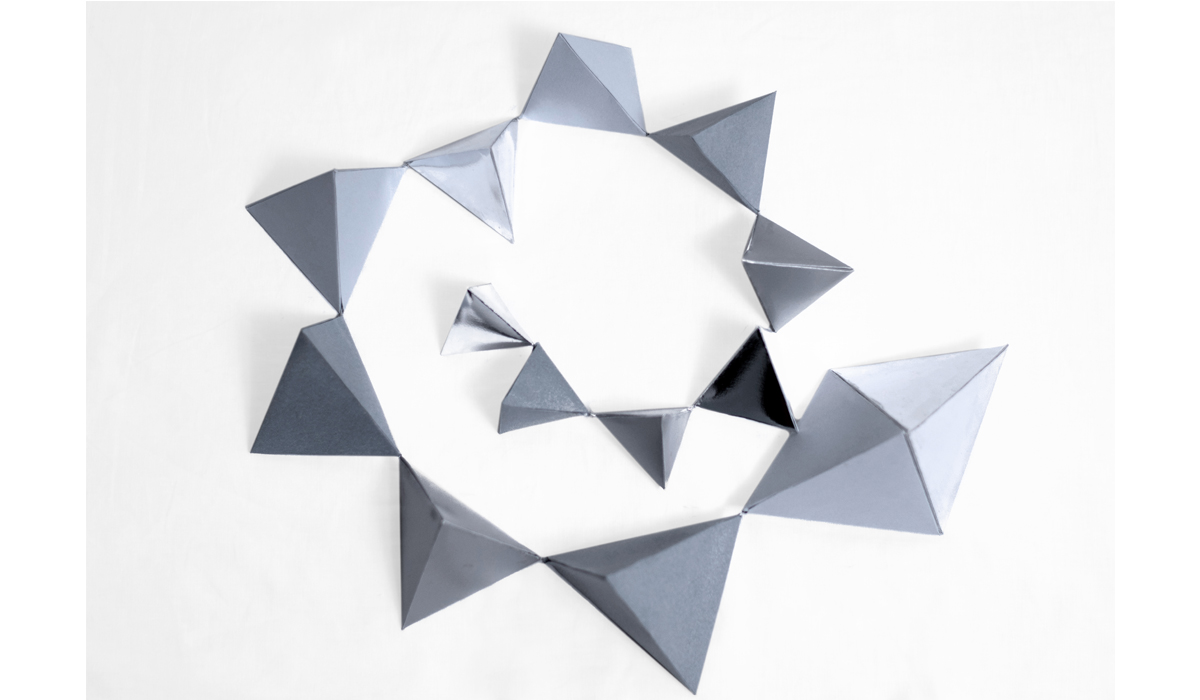

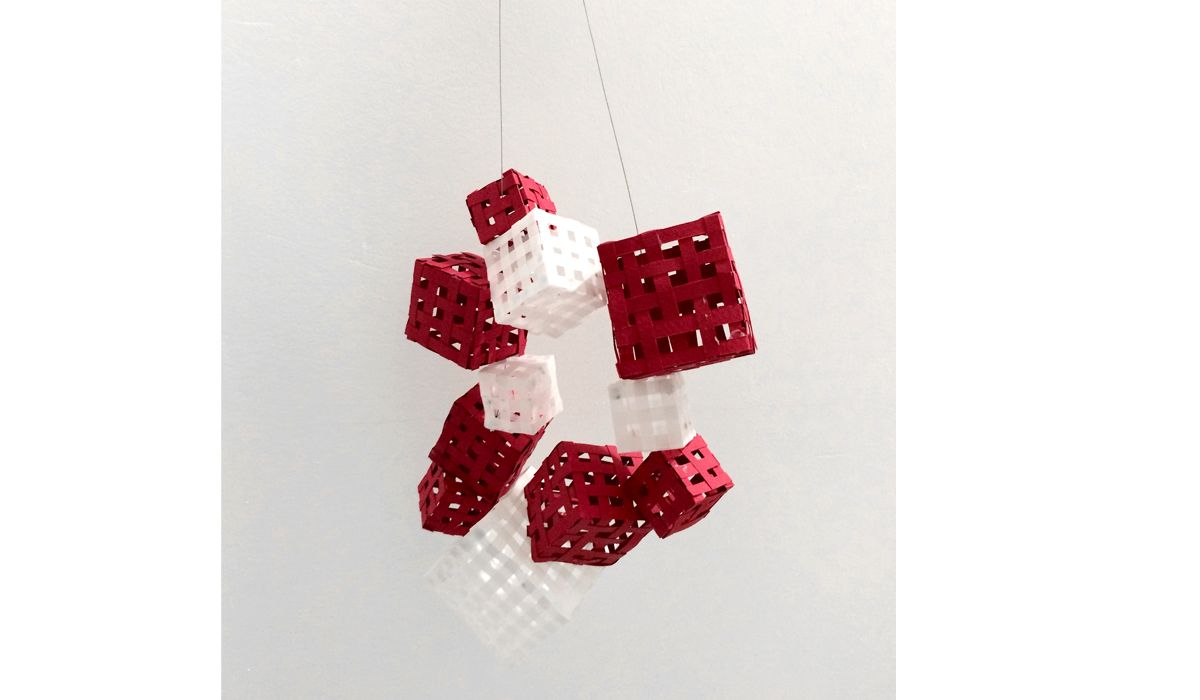

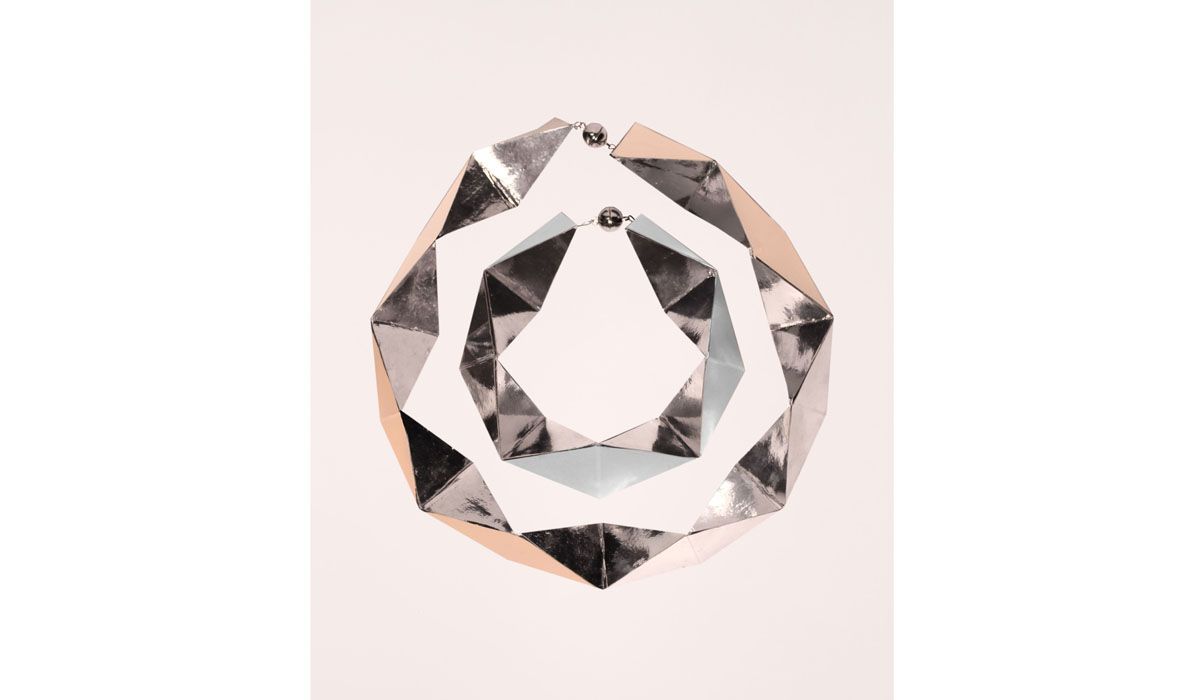

We put no restrictions on the type of material at all. The students were free to choose whichever type of paper they wanted: from thin card to laminated and printed paper, from comic strip paper to paper made from vegetable matter. As you can see from the designs, the techniques used were also extremely varied. Folded, embroidered, plaited, sewn, pleated, punched, recycled, glued, paper takes on surprising forms and is the perfect material for intriguing experimentation.

Paper jewelry: precious items made in 100% natural and eco-sustainable material. How is this concept interpreted in today's society?

Nowadays, the public finds it much easier to understand the design value of an item irrespective of the preciousness of the material in which it is made. When I dealt with paper jewelry for the first time in 2009, making jewelry with such a poor and low resistant material was not very common and the public was both suspicious and curious to see such unusual and highly untraditional items. Now, however, also due to growing attention to sustainability, that suspicion had become a desire to understand the new languages that are populating the world of ornaments.

Can you give us some historical facts about paper jewelry? Where does it originate, who are the main exponents, how has it changed over time?

As I said, in 2009 I organized an exhibition in the Triennale in which I presented over eighty gold artists and designers from all over the world who worked with paper creating extraordinary shapes, surfaces and structures. For shape, I had selected some marvelous examples, like Riccardo Dalisi's leaning surfaces in shiny tin foil, Sandra di Giacinto's audacious folding, the striking rolled cylinders by Claudia Diehl or the colored beads of the Gulu tribe. Then there were the irreverent pencils by Peter Skubic, Angela Simone's decorative feathers, Shari Pierce's pendants, which combine the lightness of paper with the gravitational strength of color. In its formal study, the call to naturalist themes was, and still is, extremely strong – from the joyful flowers by Ana Hagopian to the monochrome vegetables by Joanne Grimonprez, the softly shaded wings by Andrea Halmschlager, the ethereal petals of Caren Hartley, the virtuous compositions by Beatrix Mapalagama, precious examples of formal and chromatic harmony. Formal study is flanked by that of surface, where, like the canvas of a painting, paper becomes a submissive support for surface interventions: textures, decoration, etching, dripping or other techniques loaned from painting or photography. These items have a strong two-dimensional inclination that change their presence from heterogeneous environments, like Manon Van Kouswijck's maps, the immaculate puzzles by Ivana Riggi or the chromatic specters by the Pole, Andrzej Szadkowski. The textures by Ritzuko Ogura, where paper becomes a decoration in itself by playing on chromatic combinations and textures like corrugated or honeycomb cardboard, are particularly beautiful. Annamaria Zanella unites her usual attention to color with material studies by saturating the paper in her intense pigments, highlighting, by contrast, its fragility and delicacy. Lastly, paper becomes a structural element as well as decorative, compositional architecture and a mainstay frame. This requires total knowledge of the material and its potential. Key characteristics in the pleated masterpieces by Janna Syvanoja or the ruffs by Dutch designer, Nel Linnsen. The structural value of paper, explored in the elegance of pleating, also features in the studies of Daniele Papuli, Erica Rasmussen, Lydia Hirte, Kaoru Nakano and Noemi Gera, whose elegant collars, with their chromatic layering, also transform into sculptures able to exist outside the body.